Note: This post originally appeared on my (discontinued) Gray Box blog on Aug 30, 2012.

Wherein I report preliminary results of my inquiry into student learning in my argument-based introductory history course. (Updated at bottom with some statistical details.)

It just makes sense that my inaugural post here addresses my own work in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) in history. I’ve carried out several SoTL projects over the years — collecting and analyzing evidence of my own students’ learning — but I have for the first time collected data from a comparison group of students, and it is really interesting for me to see how my own students measure up against students in a similar course.

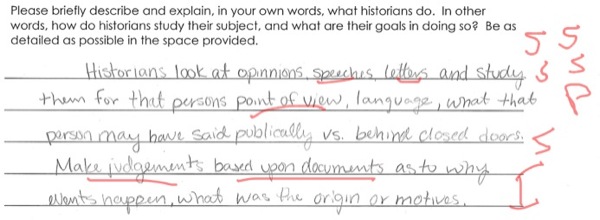

More specifically, I asked students in my introductory (early) American history course and in a colleague’s introductory (modern) American history course to explain, in their own words, “what historians do” and to give specific examples if possible.

It’s important to note that these were not questions that any of the students intentionally prepared to answer. Rather, students received a small amount of extra credit simply for responding briefly to these prompts after they completed their in-class final exams. (There was no added incentive to be especially thoughtful or complete.) In sum, I collected a set of over 150 quickly penned responses from students who were probably pretty tired of answering questions for professors.

I will have more to say about the data that I collected in due time, but I want to explain here that despite the limitations noted above, I was able to see marked differences between the responses of my students, who had just completed a question-driven, argument-based introductory history course, and responses of students who had taken a more standard history survey course (taught by an excellent teacher, by the way).

While the evidence that I collected was textual, and I will pay close attention to the language students’ used, I also analyzed the responses using a rubric, marking each one with a series of codes based upon the content of the response. (I have shared my rubric here.) I then entered the codes for each response into a spreadsheet for collective, quantitative analysis.